Cuz, even I knew the answer to Mo Cheek’s question about officer comments about the public. And its not what Chief Koval told the told the Common Council, not even close. It clearly flew in the face of his own department policies.

VIDEO OF KOVAL’S MASSIVELY INACCURATE DEPICTION THE 1ST AMENDMENT RIGHTS OF OFFICERS

Alder Maurice Cheeks: The one thing that we heard specifically was something that was brought to all of our attentions this evening is some derogatory and vulgar comments that are being ascribed to Madison Police Officers. My question to you chief is, I haven’t studied the petition to verify who said these or whether or not they are officers, but I wanted to ask you directly, if the sort of language that is ascribed to officers is becoming or acceptable of officers and if not, is this something you are going to look into and if so, are there disciplinary or other such actions that can be taken.

Chief Mike Koval: Alder, we have a policy on social media and the problem or challenge or the conundrum if you will, is that you are an employee for 8 hours a day and after that period of time, you still do not relegate any of your First Amendment rights, cuz as distasteful as some of that might be, to you and I and others of reasonable, uh, authentication on that. The key is that, yes, the matter has been referred to our Professional Standards Unit, however the only way that we would have specific venue over the item is if it could be established that they were engaged in that speech while they were on the clock or if in some shape or form they were using city resources to transmit or promulgate that. I certainly have a question that has been tendered to the city attorney’s office, asking if I am missing anything here, but at this juncture it would appear that, and I have not heard back but it is my sense that there is an awful lot of stuff that is protected speech outside of the context of workplace and I would prefer to ascribe those comments to “outliers”, its certainly not relective of the normative dispositions of the Madison Police Department.

ACTUAL OFF-DUTY USE OF SOCIAL MEDIA POLICY

The “Social Media – Off-Duty Use” policy says as follows:

This procedure serves to clarify and establish guidelines and prohibitions for MPD personnel’s personal use of social media, and seeks to mitigate negative consequences of the personal use of such technology that may have bearing on MPD personnel in their official capacities. These guidelines and prohibitions build on policy requirements put forth in the Law Enforcement Code of Ethics, Madison Police Department Mission Statement and Core Values, as well as all applicable portions of Madison Police Department Code of Conduct and Standard Operating Procedures, City of Madison Administrative Procedure Memoranda, and established City, State, and Federal Law.

MPD personnel have a duty to represent honestly, respectfully, and legally their dedication to the profession of law enforcement while on- and off-duty. MPD personnel are expected to represent the Core Values of the Madison Police Department at all times, even while using the internet for personal purposes. All MPD personnel are reminded that they are committed to act as representatives of the MPD at all times, while on and off duty, and that all policies, memos, and applicable laws governing personnel conduct also apply to conduct associated with the use of social media.

Due to the nature of the work and policies of the MPD, these standards should be expected to be more

proscriptive than those put forth in City of Madison APM 3-16. Employees will not post, transmit, share, publish or otherwise disseminate any of the following:

1. Any information gained by reason of their employment with the Madison Police Department (without permission from the Chief or designee). This includes classified or sensitive information and/or contents of police records. (See MPD Code of Conduct #21 and SOP Records Inspection and Release and City of Madison General Ordinance 3.35(5)(d).)

2. Information that would impede performance of duties, impair discipline or negatively impact the public

perception of the MPD.

3. Any images of MPD logos, uniform, or property in a manner that may negatively affect or cause reputational harm to the public’s perception of the MPD. MPD personnel are permitted to use photographs or video recordings taken during MPD-sanctioned, official ceremonies and events, such as graduation, promotional ceremonies, Honor Guard ceremonies, etc.

4. Any material that may provide grounds for undermining or impeaching an employee’s testimony.

5. Any material that endorses or promotes products, opinions or causes and that could reasonably be

considered to represent the view or position of the MPD (without permission from the Chief or

designee).Other departmental policies, procedures and directives may apply to the off-duty use of social media. The MPD will not be actively monitoring personal social media accounts of its employees. Monitoring of a personal site will only take place if a concern/complaint is brought to the attention of the MPD.

AT ISSUE

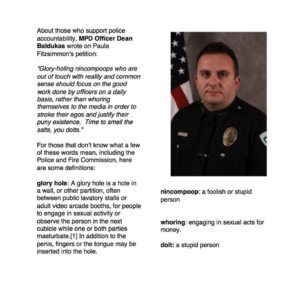

Koval was talking about this:

But since then, there’s been more. A former MPD calling Genele Laird a “pole cat” and several current officers “liking” the comment. I wonder if Assistant Police Chief Randy Gaber is all over this?

Richard Daley: There is no antiseptic, dispassionate, detached, or neutral method of taking into custody an out of control ‘pole cat’ who is violently resisting. A small crowd of publicity seeking, petulant and intent on disrupting functional law enforcement process with anarchistic tendencies has captured the limelight (BLM) Sadly some seek the limelight more than they respect the people stuck in the middle doing the hard work. Good men and women are doing their best to serve professionally and as humanely in these circumstances as the situation would allow. But, the situation didn’t allow that, and it is not the fault of the officers unfortunately called there yet doing their best. It is the fault of those that encourage this sort of belligerent behavior through distracting and unwarranted/unfounded criticism while detracting from the good work that was done. Get off the stage, DCC, our time is over!

Comment is “liked by officers” Howard Payne, Maggie Mulroy as well as former MPD employee Renee Supple. I’m pretty sure that Detective Bruce Frye had also “liked” at one point, but then it was removed – but I could be wrong about that. He comments elsewhere in the thread.

THE CITY ATTORNEY SAYS . . .

Anyways, for those of you who want to try to wade through it, here is Attorney May’s opinion showing that Koval was wrong . . . very, very, wrong. May takes a while to get there, I think hoping that the readers give up before finding out that Koval was SO VERY WRONG as were his officers. Hopefully, not dead wrong and these officers are taken off the streets before we have another killing of a resident of Madison that they seem to have such contempt for.

TO: Mike Koval, Chief of Police

FROM: Michael P. May, City Attorney

RE: Free Speech and Public Employee DisciplinePublic employers often face the difficult question of balancing an employee’s First Amendment free speech rights against disciplining the employee for statements undermining the public employer’s operations. This issue recently arose regarding certain online comments made in response to a petition supporting the City of Madison police department.

The following analysis sets forth the framework for determining when employees may be disciplined for public statements that may be protected by the First Amendment. This analysis discusses situations where discipline was upheld even when the employee’s statements were made when off duty.

I. PROTECTED SPEECH UNDER THE FIRST AMENDMENT: THE CONNICK- PICKERING TEST.

The balancing of public employee free speech rights and public employer interests is well developed law, and the issue is well summarized by this statement in a case from the Second Circuit Court of Appeals:The Government as employer bears a special burden. Absent contrary legislation, a private employer may regulate the workplace environment, and hire, fire and promote as it pleases. The Government enjoys no such freedom. . . . The government as employer may not discriminate arbitrarily, regardless of the statutory regime . . . and conspicuously unlike a private employer, it must respect its employees’ First Amendment right to free speech.

…

[e]ven the Government as an employer, and hence a consumer of labor, must retain some freedom to dismiss employees who do not meet the reasonable requirements of their jobs.Locurto v. Giuliani, 447 F. 3d 159, 163 (2d Cir. 2006) (internal citations omitted).

The preliminary inquiry is whether the employee’s speech was made pursuant to that person’s official duties, i.e., was the speech part of the employee’s duties as a public employee? If that is the case, then such speech is not protected by the First Amendment, discipline may be imposed and the inquiry ends there. Garcetti v. Ceballos, 574 U.S. 410 (2006). (Footnote: For a recent case that summarizes the state of the law and applies a Garcetti ban on employee claims, see Kubiak v. City of Chicago, 810 F. 3d 476 (7th Cir. 2016). There are numerous Garcetti type cases; this memo will not discuss further that line of precedent.)

Determining whether a public employee’s speech, made outside of their official duties, is protected by the First Amendment involves a two-part inquiry known as the Connick- Pickering test. Connick v. Myers, 461 U.S. 138, 103 S.Ct. 1684 (1983); Pickering v. Board of Educ. of Township H.S. Dist., 205, 391 U.S. 563, 88 S.Ct. 1731 (1968). The first element of that test involves determining whether the employee’s speech addressed a “matter of public concern.” If the speech addressed a matter of public concern, then the Pickering balancing test is applied to determine whether “the interests of the [employee] as a citizen in commenting upon the matters of public concern” are outweighed by “the interest of the state, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees.” As a government employer, the City must be mindful of the “Connick-Pickering” analysis and include that analysis as part of its internal investigatory process.

A. THE CONNICK PUBLIC CONCERN TEST

1. Matters of Public Concern – FactorsIn determining what are matters of public concern, the Seventh Circuit considers “the content, form, and context” of the speech at issue. Button v. Kibby-Brown, 146 F.3d 526, 529 (1998) (relying on Connick, 461 U.S. at 147-48.)

Factors to consider in making this determination include:

• whether the expression relates to an issue of political, social, or other concern to the community.

• whether it relates to matters only of personal or private interest.

• whether the employee attempted to have the subject of his or her expression aired in a public forum.

• the motivation of the employee in making the expression.It is not dispositive that the speech involves a subject of substantial public interest (e.g., government waste; misuse of police resources). For if the employee’s sole motive in discussing such a subject was to promote a purely private interest, the speech is not entitled to First Amendment protection. Similarly, a private venue does not conclusively establish the speech was solely a matter of personal interest; matters of public concern can be discussed in private, such as on a personal FaceBook page. Courts consider both the content and the context of the speech at issue.

2. Matters of Public Concern – Examples

The Courts have broadly interpreted the range of speech encompassed in the term “matters of public concern.” Here are but a few examples of speech addressing matters of public concern:

• Allegations of favoritism within the Fire Department and lenient disciplinary action taken against supervisor. Greer v. Amesqua, 212 F.3d 358 (7th Cir. 2000)

• Whether public officials are operating the government ethically and legally. Greer, supra

• Police protection and police safety (in the context of speech about how police investigations were to be conducted and how the balance between individual officer initiative and central control was to be struck). Gustafson v. Jones, 290 F.3d 895 (7th Cir. 2002)

• Proper allocation of police patrols and other departmental resources. Campbell v. Towse, 99 F.3d 820 (7th Cir. 1996)

• Comment by employee in constable’s office when hearing of the attempted assassination of Reagan: “If they go for him again, I hope they get him.” Rankin v. McPherson, 438 U.S. 378 (1987).

• Chronic time abuse by public employees (which implicates misuse of tax funds). Sullivan v. Ramirez, 360 F.3d 692 (7th Cir. 2004)

• Speech on radio talk show involving extremely critical comments regarding the local criminal justice system (made by a probation officer who identified himself as “George,” a local gang member). Jefferson v. Ambroz, 90 F.3d 1291 (7th Cir. 1996)

• Arguments with abortion protesters over their methods (by an off duty police officer). Lalowski v. City of Des Plaines, 789 F. 3d 784 (7th Cir. 2015).

• Police officer made comments in a newspaper column that were “caustic, offensive, and disrespectful” to minorities, women and the homeless. Nixon v. City of Houston, 511 F. 3d 494 (2007).An employee speaking out on a matter of public concern is engaging in protected speech under the First Amendment, unless the employer’s interest in regulating or prohibiting the speech outweighs the employee’s First Amendment rights. This is the second part of the analysis, the Pickering balancing test.

3. Matters of Private Concern—Examples

Generally, the courts find that a topic is a matter of private concern when an individual is pursuing a personal matter related primarily to him or her, not to the public:

● Complaints characterized as “a single employee upset with the status quo.” Garziosi v. City of Greenville, 775 F. 3d 731 (5th Cir. 2015).

● Complaints by police officer were to “further her personal interest in remedying an employee grievance.” Kubiak v. City of Chicago, 810 F. 3d 476 (7th Cir. 2016).An employee speaking out on a matter of private concern is not engaging in speech that is protected by the First Amendment.

B. THE PICKERING BALANCING TEST

1. Pickering Test – Factors

A government employer is not foreclosed from disciplining an employee simply because the employee speaks out on a matter of public concern. To determine whether the employer may take such actions involves the second element of Pickering balancing test. Factors to consider in determining whether an employee’s free speech rights are outweighed by the employer’s right to promote the efficient delivery of public services include:

(1) whether the statement would create problems in maintaining discipline by immediate supervisors or harmony among co-workers;

(2) whether the employment relationship is one in which personal loyalty and confidence are necessary;

(3) whether the speech impeded the employee’s ability to perform daily responsibilities;

(4) the time, place, and manner of the speech;

(5) the context in which the underlying dispute arose;

(6) whether the matter was one on which debate was vital to informed

decision making; and

(7) whether the speaker should be regarded as a member of the general

public.Additionally, particularly with respect to Police and Fire agencies, courts also give weight to whether the speech would disrupt operations of the department by degrading the department’s standing or reputation with the community it serves. Courts recognize that such agencies require the confidence and cooperation of the public in order to deliver effective services.

2. Pickering Test – Examples.

Using the cases cited above, here are examples of the court’s application of the Pickering balancing test :

● In Greer, the court determined that the employer’s interest in disciplining Greer for his inflammatory press release outweighed Greer’s interest in speaking out about a matter of public concern (favoritism). The factors that the court considered most significant included: the manner and means of Greer’s protest; the fact that Greer never approached the Chief or his supervisors regarding the incident and did not pursue internal avenues for questioning the department’s investigation; that Greer issued a press release based on speculation; that Greer circulated his unsubstantiated accusations to mass media outlets for broad public consumption, intending to indict the integrity of the department’s leadership publically; that Greer’s press release led directly to the publication of a front page newspaper story; that the department reasonably concluded that Greer’s speech, if left unpunished, would disrupt the operation of the department by degrading the department’s standing with the public, undermining the Chief’s authority and inciting disharmony within the department’s ranks. (Footnote: The court rejected Greer’s argument that his news release did not ignite actual disruption in the workplace. The court noted that an employer need not establish actual disruption before disciplining an employee when the threat of future disruption is obvious. The court further noted that courts give substantial weight to a government employer’s reasonable predictions of disruption.)● In Gustafson, the court struck the balance in the employees’ favor. The factors the court considered of greatest significance included: the content of the message (police protection and public safety in a large metropolitan area); the manner and means of the employees’ protest, specifically that the employees went up the internal chain of command and then to their Union leadership prior to going public; that the decision to go public was only after the employees concluded that disclosure was necessary given the nature of their concerns and their supervisor’s unwillingness to do anything further about the directives; that there was no evidence in the record that the employees’ speech had any disruptive effect on the department, nor was there evidence the Chief reasonably believed the speech would have future disruptive consequences; that the case did not involve a mere personal grudge against supervisors. (Footnote: The balancing test is not a mere theoretical exercise but depends on the actual facts in the record. The court noted, “In the end, this is a case of failure of proof, and should be taken as no more than that.” Specifically, the Milwaukee Police Department was unable to connect the speech of the employees on a matter of public concern to disruption in the workplace.)

● In Rankin, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that a low-level noncommissioned employee in a Texas Constables Office had a First Amendment interest in making her casual statement that was not outweighed by the employer’s interest in discharging her for making the statement. Here the manner, time and place of the speech was of substantial importance: the statement was made in a private conversation between the employee and her coworker boyfriend; the statement was simply overheard by a coworker; there was no suggestion that any member of the general public was present or heard the employee’s statement; in that context, the court found it very difficult to conclude that the statement interfered with personnel relationships or the speaker’s job performance to such an extent that the State’s interest outweighed First Amendment rights.

● In Sullivan, the employee’s interest in recording the comings and goings of her coworkers in order to substantiate her complaint regarding what she perceived to be their unexplained and inappropriate absences was outweighed by the employer’s interest in workplace harmony. The court considered the context of the speech as being the most significant factor: specifically, the employee gratuitously assumed an unofficial managerial role.

● In Jefferson, the court concluded that the employee’s free speech interests were outweighed by the employer’s interests. Significant factors included: the information involved unwarranted and unfounded accusations about the handling of a case by Rockford Police Department; the case was very sensitive and currently in the middle of a criminal trial; the comments damaged the Illinois Probation Offices’ relationship with Rockford Police Department; the probation officer’s comments negatively impacted his ability to do his job (supervising probationers and insuring that the probationers complied with the orders of the court). (Footnote: Note that the court held there is no requirement that the employee act with specific intent to harm. The fact that the probation officer did not anticipate being caught was also found to be of little relevance.)

● In Lalowski, the court concluded that the officer’s profane rant against the abortion protesters was not protected by the First Amendment, and the City’s interests in maintaining good relations with the public was paramount. “Lalowski’s speech directly conflicted with his responsibilities as a police officer because one of those responsibilities was to foster a relationship of trust and respect with the public. … By attacking private citizens with profane and disrespectful language, Lalowski compromised the community’s trust in its police officers, thus failing in one of his most important duties.” Although the officer was off duty, he had previously approached the protesters while on duty, so he was identified as a police officer.

● In Nixon, the court again sided with the City of Houston because the caustic comments in the news articles would injure the police department’s relationship with broader community. Nixon predates the Lalowski decision, but it further demonstrates the importance for police departments to maintain good relations with the community. The court noted that it mattered not that Nixon was off duty when he wrote the articles because he self-identified as a Houston police officer in the articles.

● One of the seminal cases concerning punishment of police officers and firefighters for off duty speech is Locurto v. Guiliani, 447 F. 3d 159 (2d Cir. 2006). An NYPD police officer and two NYFD fire fighters participated annually in a parade in their nearly all- white home town. They were part of a float that was supposed to be a humorous parody, but often used ethnic groups as the butt of the jokes (“Hasidic Park” and “Happy Gays” were two themes in prior years). This year, the float featured two large Kentucky Fried Chicken buckets, with officers parading in black face and afro wigs, eating watermelon. Although there was no identification of the officers as NYPD and NYFD employees, the float got a lot of publicity and the officers were identified in, among other places, a story in the New York Times. In upholding the firing of the officers, the court (with some misgivings) assumed the speech was about a matter of public concern to give the officers the most protection under the Connick-Pickering analysis. In applying the Pickering balancing test, the court stated the rule about employees whose jobs entail significant contact with the public (Id., at 178-79):

“Police officers and firefighters alike are quintessentially public servants. As such, part of their job is to safeguard the public’s opinion of them, particularly with regard to a community’s view of the respect that police officers and firefighters accord the members of that community. …

[a] Government employer may, in termination decisions, take into account the public’s perceptions of employees whose jobs necessarily bring them into extensive public contact. …

Where a Government employee’s job quintessentially involves public contact, the Government may take into account the public’s perception of that employee’s expressive acts in determining whether those acts are disruptive of the Government’s operations.”

II. CONCLUSION

Government employers, unlike their private counterparts, are subject to restrictions in disciplining their employees for the content of their speech. The First Amendment prohibits the government from abridging speech and thus, protects public employees’ rights of free speech. The United States Supreme Court has approved a framework to examine when and whether public employees may be disciplined for exercising their First Amendment rights, called the Connick-Pickering analysis. This analysis is very fact intensive, as demonstrated by the results of some of the cases noted above. In considering discipline for employees’ exercise of First Amendment rights, the City needs to recognize and apply the Connick-Pickering analysis.CC: Mayor Paul Soglin

Asst. Chief Sue Williams

Gloria Reyes

Patricia Lauten

All Alders

Lt. Amy Chamberlin

Brad Wirtz

Marci Paulsen

CONCLUSION

Now Chief Koval allegedly graduated from law school, and he approved the Code of Conduct and the Standard Operating Procedures. I can’t see any way he could have said what he said at the Common Council meeting, he had to know there were both policy and legal concerns here. And I hope he didn’t teach this unit of the training!!!! Yikes. None of what he said was even close. Now, the only question is, is he a liar, or incompetent? Personally, I can’t believe a word the man says. He doesn’t seem very truthful.